Australia faces three significant challenges to its long term economic prosperity and environmental sustainability.

First, we are not on track to achieve our appropriate contribution to the world reaching net zero by 2050. Second, Australia has a structural budget deficit but needs significantly more revenue for housing and other social policy. Third, Australia’s economic fundamentals are weak: productivity is low, and future prosperity requires increased investment in industries in which Australia has a comparative advantage.

The Case for a Price on Pollution sets out policies that can deliver emissions reduction and economic renewal together – a package that is fair, efficient and politically durable. It puts two ideas at the centre:

Together, the Polluter Pays Levy and the Fair Share Levy would collect average revenue of $35.6 billion each year between 2026 and 2050.

Part of this revenue can be used to generously compensate households for higher energy prices, with the remainder being used to strengthen the budget, support social policies such as housing, and to fund investment in the green industries that will underpin Australia’s future productivity and prosperity.

Together, the Polluter Pays Levy and Fair Share Levy would raise an average of $35.6 billion per year

Australia’s Trilemma

1. Emissions reductions are too slow

Climate change is a grave and growing threat to global ecosystems and to economic life. Warming above 1.5ºC will damage the environment and many parts of the economy. Some effects will be irreversible, and the risks to people and natural systems increase with average temperatures. The window to secure a safe, liveable future is closing.

Australia has committed to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, and to reducing emissions 43 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030. The Government has also pledged to reduce emissions between 62 and 70 per cent below 2005 levels by 2035.

But Australia is not reducing emissions at the speed required to meet either its 2030 or 2035 targets, or to satisfy its Paris commitment to efforts that would limit warming to 1.5°C.

Australia is not on track to meet its climate targets

Since 2005 emissions have barely decreased outside the land-use sector, and in some sectors they have increased.

Sectors representing nearly 40 per cent of Australia’s emissions in 2005 have not even begun to reduce. Transport emissions have risen by more than 20 per cent, industry by about 7 per cent and stationary energy by more than 20 per cent. Almost all progress has come from land-use change.

Beyond land use, Australia’s emissions have broadly remained flat

Meanwhile, the economic costs and threats to Australia posed by global warming are significant and already visible. More frequent extreme weather events are pushing up insurance costs, disrupting supply chains and reducing productivity.

It is estimated that by 2050, the cumulative cost of reduced agricultural and labour productivity alone will reach $211 billion. These costs will continue to grow as temperatures rise.

Australia’s current emissions-reduction policies are inefficient because they are narrow and fragmented, with large gaps in coverage. Some facilities and sectors are required to reduce emissions while others are not. When firms face different abatement requirements and bear different costs of abatement, the collective cost of reducing emissions is higher than necessary.

The current policy mix is also expensive for the budget. Individual policies are at best budget-neutral, and none raise revenue to support households, invest in clean industries, or help fund the transition to net zero.

Safeguard Mechanism

The goal of the Safeguard Mechanism (SGM) is to reduce emissions from facilities that emit more than 100,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent each year. A firm’s total emissions must not exceed an emissions-intensity baseline, multiplied by the number of units produced. If a firm’s emissions are less than the total permitted by their baseline, these savings are recorded as Safeguard Mechanism Credits (SMCs), which can be sold or banked for future compliance. If a firm exceeds the total number of emissions associated with their baseline, they can buy Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs) or SMCs to offset excess emissions.

The SGM in its current form captures only 30 per cent of Australia’s emissions. Even if it were broadened, it has inherent limitations and weaknesses that make it far inferior to carbon pricing.

First, the SGM creates substantial costs to the budget but does not raise revenue. Second, it undermines market allocations of resources. Emissions intensity baselines are centrally determined and become increasingly complex as coverage expands. It is not possible for agencies to specify these accurately and fairly for all industries, resulting in wealth transfers between sectors and distorting investment decisions. Lastly, an expanded SGM will have distributional impacts. This is true of any carbon price, but because the SGM doesn’t generate revenue, these equity impacts cannot be corrected without imposition on the budget.

Capacity Investment Scheme

The Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS) is the main policy for achieving the Federal Government’s 82 per cent renewable energy target for 2030. It aims to deliver 40 GW of new renewable energy capacity and storage through a tender-based process. 20GW of capacity has been awarded through tenders, but less than 3GW of capacity has commenced construction or been commissioned.

The CIS is a handbrake on investment outside the scheme as it distorts competition between projects inside and outside of the scheme. It also transfers price risk from private investors to the government.

The New Vehicle Emissions Standard

The New Vehicle Emissions Standard (NVES) targets the 10 per cent of emissions produced by light vehicles. It places an emissions ceiling on the average emissions-per-kilometre of vehicles sold each year. The ceiling ratchets down to reduce emissions from new cars and SUVs more than 60 per cent by 2030, and emissions from vans and utes by 50 per cent.

The NVES is a step in the right direction, but there is no clear pathway to net zero beyond 2030, and the NVES does not create incentives to reduce emissions from existing vehicles. Reflecting the fragmented nature of abatement policies, the NVES coexists with expensive tax exemptions for electric vehicles, which are estimated by the Parliamentary Budget Office to cost billions of dollars over the coming decade.

2. Australia's budget is under pressure

Under current policies, Australians can expect a decade of budget deficits.

Apart from a brief period between 2022 and 2024, Australia has not enjoyed a sustained or substantial budget surplus since 2007–08. Budget projections do not point to a surplus until 2034–35, and these projections presume that some large commitments sunset on their scheduled dates.

Sustained structural budget deficits are a warning that the economy is not built on strong foundations, because government expenditure regularly exceeds government revenues. When annual deficits are not balanced by surpluses through time, the government accumulates debt. The Federal Budget is forecast to add nearly $152 billion to gross debt over the next four years, at a rate of between $35b and $42b per year.

Australia’s budget isn’t expected to reach surplus until the mid-2030s

Structural pressures include rising interest payments on government debt, and rising expenditure on the NDIS, defence, hospitals payments, medical benefits payments, the Child Care Subsidy and aged care payments.

The forecast return to surplus requires the Government to hold expenditure steady – by finding savings elsewhere – and for economic growth to lift revenue.

If the government cannot hold expenditure steady, or if revenues do not increase, the return to budget surplus will not occur.

3. Australia has a productivity problem

Productivity growth is the engine that lifts wages and living standards over the long term. A more ‘productive’ economy can turn a given set of resources – labour, skills, energy, and materials – into a greater volume and quality of goods and services. All else equal, this raises general living standards.

Australia has had a persistent productivity problem over the past decade. In the past 10 years, productivity grew by less than a quarter of its 60-year average. Measures of long-term productivity growth, based on a twenty-year average, have been falling steadily since the early 2000s.

Low levels of investment lead to ‘capital shallowing’, weakening productivity growth. One reason Australian labour productivity has fallen is the low level of capital investment in non-mining sectors. Long-term low levels of investment in capital expenditure has contributed to almost flat labour productivity over the past decade.

Australia’s weak productivity leaves no room for wasteful policies: policies to reduce emissions and raise revenue need to be ‘productivity neutral’ or ‘productivity positive’.

Prosperity in a decarbonising world

will require new policies

Australia needs new and better policies to reduce its carbon emissions. It needs a stronger budget. And it needs to achieve these goals urgently and as efficiently as possible, to lift productivity and enhance Australians’ welfare.

Most major economies have committed to achieving net-zero between 2045 and 2070, with commitments covering three quarters of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Decarbonising the global economy by 2050 is important for avoiding the insecurity and disorder from unmanageable climate change. It is also necessary for Australia’s future prosperity.

Australia has a remarkable economic opportunity in a decarbonising world. Its renewable energy, mineral, and other natural resources give it a comparative advantage in producing and exporting zero-carbon, energy-intensive goods such as green iron, aluminium, silicon, ammonia and fuels. These industries have the potential to underpin a new era of export-led prosperity.

Australian green exports would also contribute to global emissions reductions. Greenhouse gas emissions from energy-intensive industries and the production of transport fuels represent a significant share of global emissions. At scale, Australia’s green exports could make a substantial contribution to global decarbonisation.

Seizing this opportunity requires public investment. Early producers will need innovation support, government will need to help bridge the ‘green premium’ price gap, and substantial investment is required in transmission, ports, storage and other shared infrastructure.

This report sets out a policy framework designed to meet these needs. It proposes two complementary reforms that price carbon pollution and secure a fair public return from Australia’s gas resources.

Together, these reforms reduce emissions at lowest cost, deliver substantial cost of living support for Australian households through the transition, and create the fiscal strength needed to invest in Australia’s clean industrial future.

Polluter Pays Levy: Making polluters pay for climate damage

The Polluter Pays Levy is a straightforward ‘polluter pays’ tax on the carbon embedded in fossil fuels extracted or imported for use in Australia.

Under the Polluter Pays Levy, companies are liable for both the ‘fugitive’ emissions released during fossil fuel extraction and the carbon dioxide emissions that will be released when those fossil fuels are combusted. For example, when coal is mined and sold, methane is released during the mining process and carbon dioxide is later emitted when the coal is burned for electricity. The PPL makes the company responsible for the methane and carbon dioxide emissions associated with its product.

Applied to around 140 extraction sites operated by fewer than 60 companies, the Polluter Pays Levy covers more than 80 per cent of Australia’s emissions – well above the 30 per cent currently covered by the Safeguard Mechanism and the 34 per cent covered by policies for the electricity sector. This broad coverage allows the market to identify more low-cost abatement opportunities, and the end of expensive, piecemeal policies.

By targeting a small number of firms responsible for products associated with the majority of emissions, the Polluter Pays Levy is simple, transparent, and difficult to game.

The PPL price would begin in 2026 at $17 per tonne of CO₂-equivalent, with the price rising until it meets the EU carbon price in 2034. From 2034 it should follow the EU carbon price.

The domestic PPL price should be accompanied by a carbon levy applied at the border to energy-intensive imports, so domestic producers of energy-intensive goods are not disadvantaged. This border levy should be based on the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

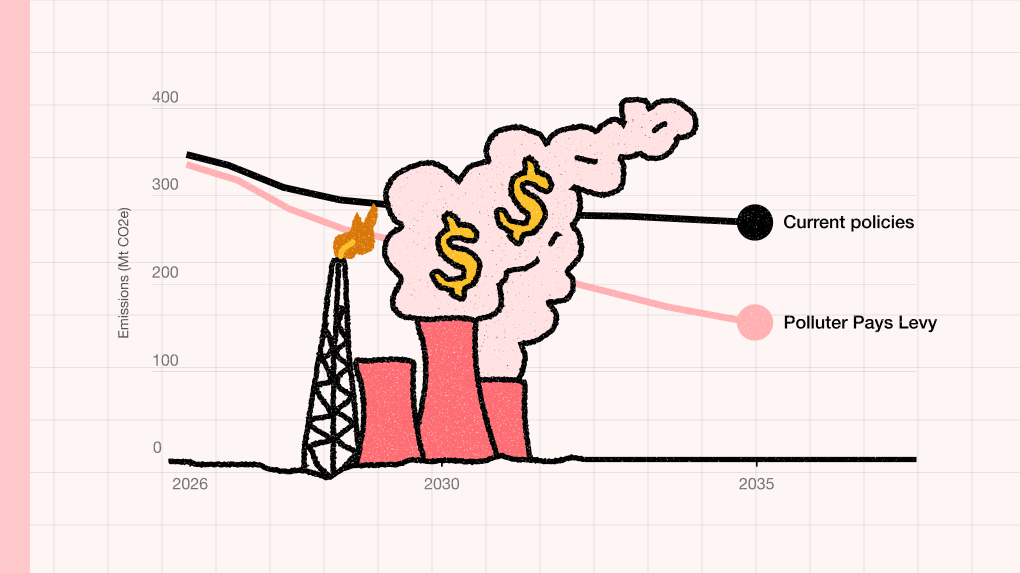

Modelling by the Centre of Policy Studies shows the PPL would cut emissions far faster than current policies. It would deliver about 100 million tonnes of additional annual abatement after the first ten years, and more than double the total reductions expected under current policies.

A Polluter Pays Levy achieves deeper emissions reductions than current policies

The Polluter Pays Levy also raises significant revenue. It generates an average of $22.6 billion per year from 2026 to 2050. This is more than enough revenue to make sure households are insulated from higher energy bills, and are better off compared to life under net-zero policies that do not raise revenue.

About half of Polluter Pays Levy revenue should be returned to the public in the first decade

Household Energy Compensation Payment

We recommend a Household Compensation Payment to cover conservative estimates of increases in energy bills, and a Household Support Package to cover cost-of-living concerns and to support the net-zero transition.

Households will be exposed to higher gas, petrol, and diesel prices until they have electrified. People will electrify their houses progressively, adopting new technologies as costs fall.

As households make this transition, we estimate that it will cost an average of $4.1 billion each year, between 2026 and 2050, to compensate for higher energy costs. In total this package would be worth an average of $330 per household between 2026 and 2050, peaking at about $500 per household in 2033.

Household Support Package

In addition to the Household Energy Compensation Payment, we recommend a Household Support Package to provide further assistance to households that are more exposed to energy-related cost-of-living pressures.

Households will electrify progressively over time, but around 60 per cent of households face at least one barrier to electrification. These barriers include renting, living in apartments, or facing practical and coordination challenges that make it harder to switch from gas and petrol to electric alternatives. As a result, some households will remain exposed to higher energy costs for longer.

We recommend committing $4 billion per year to household support for the first decade of the Polluter Pays Levy. This support should be targeted to households on lower incomes and those facing practical barriers to electrification, who spend a larger share of their income on energy.

Small Business Energy Compensation Payment

The Polluter Pays Levy will lead to higher energy prices for businesses, including higher gas, petrol, diesel and electricity costs. Small businesses are particularly exposed to these increases, as energy costs can make up a large share of overall business expenses, and opportunities to avoid cost increases may be limited.

From 2023 to the end of 2025, the federal government provided support to eligible small businesses through the Energy Bill Relief Fund (EBRF). In December 2025, the government confirmed that this support would not be extended beyond 2025.

To insulate eligible small businesses from energy bill increases under the Polluter Pays Levy, we recommend continuing this support using PPL revenue. Specifically, we propose a Small Business Energy Compensation Payment of $325 per year per eligible small business, consistent with the EBRF. This would require around $325 million per year of PPL revenue and would support around one million eligible small businesses.

Net revenue and economic benefits

After the Household Energy Compensation Payment, the PPL delivers an average of $18.5 billion in net annual revenue through to 2050 – enough to provide additional support for households and small businesses, to strengthen the budget, and support public investment.

Economically, the Polluter Pays Levy is highly efficient. For more than a decade it delivers net welfare gains even before accounting for climate benefits. It remains a more efficient way to raise revenue than income tax for most of its operation. Once the social benefits of reduced emissions are included, the Polluter Pays Levy is welfare positive through to 2050 – and these estimates are conservative, as they do not capture gains from repealing costly subsidies or avoiding international carbon tariffs.

Simple, transparent and hard to game, the Polluter Pays Levy targets major polluters, protects households, raises revenue and provides a credible pathway to net zero.

“There is more than enough revenue to make sure households are insulated from higher energy bills, and are better off compared to life under net-zero policies that do not raise revenue.”

Fair Share Levy: Getting a fair share of Australia’s gas resources

Fossil fuels generate extraordinary private profits, but Australia captures far less public value than comparable export countries.

Between 2020 and 2023, Australia retained only around 30 per cent of coal and gas profits, through a combination of corporate tax, royalties and the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax (PRRT). Other major fossil-fuel-exporting countries captured a much larger share of these profits – typically between 75 and 90 per cent – including Norway, Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom.

Australia captures a small share of fossil fuel profits

Australia’s existing rent tax on oil and gas, the PRRT, was introduced in the 1980s and intended to capture 40 per cent of economic rents – the above-normal profits earned after corporate tax. However, as Treasury has noted, the PRRT is poorly suited to Australia’s LNG industry and will never capture the expected profits, because the accumulation of carry-forward deductions, compounded by uplifting, can defer tax payments indefinitely.

Australian Treasury“The PRRT has been found to be better suited to oil projects rather than LNG projects since the accumulation of a large stock of carry-forward deductions, compounded by uplifting, can defer the payment of PRRT indefinitely.”

One way to raise revenue from fossil fuel production is to impose a tax on exports, but this would increase the price of Australian exports in world markets and raise concerns about energy security among trading partners. This report therefore favours taxes on large fossil fuel profits as a more economically efficient and geopolitically sensitive way to raise revenue, while giving Australians a fairer return from publicly owned resources.

A Fair Share Levy (FSL) would change this. Modelled on Norway’s ‘Special Tax on Petroleum Income’, it is a two-way cashflow tax on economic rents – the above-normal profits earned by gas producers. Because rent taxes leave normal returns untouched, they do not affect future incentives to invest or trade, or Australia’s international competitiveness, nor do they increase prices.

Norway keeps a far larger share of oil & gas revenue than Australia

Unlike conventional taxes, an FSL does not generate appreciable efficiency losses. Because profits from the Australian oil and gas industry are overwhelmingly exported to foreign shareholders, when these profits are taxed Australians receive the full benefit of the public revenue, while a substantial share of the tax burden is borne offshore.

As a result, the welfare impact of the FSL is exceptionally positive: each dollar raised increases Australian welfare overall, rather than reducing it through economic distortions, as occurs with taxes such as the GST or personal income tax.

A Fair Share Levy would raise $13 billion per year, on average, from 2026-2050

An FSL of 40 per cent would lift Australia’s effective take on fossil fuel profits to around 58 per cent, still at the lower end of global norms. It would raise an average of around $13 billion a year through to 2050, providing stable revenue to strengthen the budget and support investment in Australia’s future prosperity.

Had a FSL been in place between 2020 and 2024, it would have raised around $80 billion in additional revenue.

A Fair Share Levy would have raised nearly $80 billion between 2020 and 2024

“Because profits from the Australian oil and gas industry are overwhelmingly exported to foreign shareholders, when these profits are taxed Australians receive the full benefit of the public revenue, while a substantial share of the tax burden is borne offshore.”

Securing public support for reform

In October 2025, The Superpower Institute commissioned Redbridge Group to conduct national quantitative and qualitative research into community attitudes to climate action, cost of living, and economic reform.

The research shows that public support for pricing pollution is shaped primarily by cost-of-living pressures and perceptions of fairness. Cost of living is the dominant lens through which voters assess policy. Climate change remains personally relevant for many Australians, but it is secondary to household financial security, particularly in an environment of sustained economic pressure.

Concerns about rising bills and the risk that costs will be passed on to households are a consistent source of scepticism. Many voters expect that the costs of climate policy will ultimately be borne by households, and levels of trust in government to manage these impacts are low.

Within this context, fairness is a strong driver of support for reform. The research finds very high agreement (87 per cent) with the proposition that Australians deserve a better return from the sale of their natural resources. A levy on large polluters attracts majority support (68 per cent), including across regional areas. Support for these principles is strongest among younger voters, but is evident across age cohorts and voting groups.

The research highlights the importance of who pays. There is little support for households bearing the primary burden of emissions reduction. Voters are more receptive to policies that place responsibility on large polluters and resource exporters, particularly where revenue is directed to household support, public services, and investment.

The Polluter Pays Levy and Fair Share Levy reflect these principles in their design. Both focus responsibility on large emitters and resource exporters rather than households, while generating public revenue that can be used to support households, strengthen public finances, and invest in Australia’s economic transition. In this way, the policies align with public expectations around fairness and cost-of-living protection, while addressing the structural challenges of emissions reduction, budget repair, and long-term economic resilience.