Australia faces three related economic challenges: we are not on track for net zero, the federal budget faces a structural deficit, and productivity growth has stalled. After more than a decade of policy churn, emissions outside the land sector have barely moved.

At the same time, industry groups including the Australian Industry Group and the Minerals Council have rightly warned in The Australian Financial Review that expanding current climate policies risks greater complexity, higher compliance costs and failure to deliver the emissions reductions we need.

But the answer to this dilemma is not weaker ambition; it’s simpler reform by focusing on the principle of “polluter pays” – ensuring those who impose climate costs face them directly. This will cut emissions at the lowest cost while raising revenue to ease cost-of-living pressures and strengthen the economy.

In practical terms, this means two reforms which the Superpower Institute is proposing: a “polluter-pays levy” applied upstream to coal, oil and gas producers and importers, and a “fair-share levy” on gas producers to ensure Australians receive a fair return from their own resources. Together, they cut emissions, raise substantial revenue and reduce policy complexity, without placing new burdens on households.

Selling reform today requires recognising a changed electorate. Gen Z and Millennials are now the dominant voting bloc and are economically insecure, exposed to climate risk and focused on fairness. They are sceptical of policies that raise household costs while allowing large polluters and exporters to escape meaningful contribution.

As a result, today’s voters want a fair go. And increasingly, they feel the system is failing to deliver it.

To sell big reform to this new Australia, we must stop treating climate policy and cost-of-living relief as competing priorities. Research commissioned by the Superpower Institute and conducted by Redbridge Group shows reform earns social permission only when it links the two.

The research reveals that reforms that burden households face scepticism, while those that ask large polluters and exporters to contribute more are viewed very favourably. Within that frame, mechanisms such as pricing pollution alongside support for households and securing a fairer return from gas exports become politically viable. They appeal because they are simple, economy-wide and low-cost to administer, rather than complex regulatory overlays.

To win back trust, climate policy must be framed as an economic dividend.

“This approach targets economic rents rather than productive activity, preserving investment incentives while ensuring Australians receive a fair return.”

Australians are not blind to international comparisons. They know that Australia’s resources are undertaxed, and that the citizens of comparable fossil-fuel-rich countries such as Norway benefit greatly from their resource wealth. Norway taxes its oil and gas industry at 78 per cent and has a trillion-dollar sovereign wealth fund; Australia taxes the same companies at a fraction of that.

Against this backdrop, the Superpower Institute’s twin proposals offer a simple, credible response.

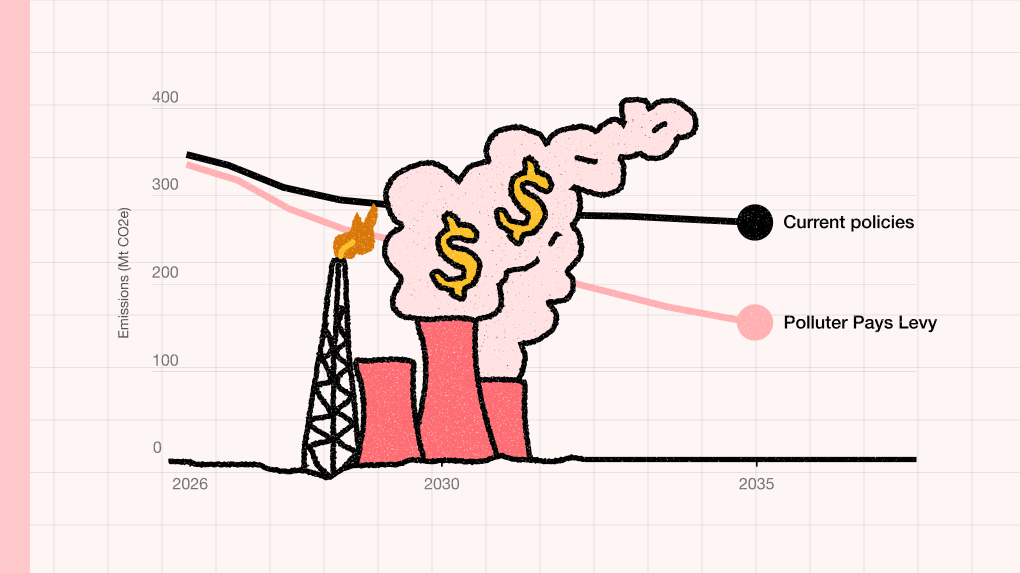

First, a polluter-pays levy is a broad-based levy on coal, oil, and gas producers to replace complex, inefficient schemes, with revenue redirected to more than compensate households for energy price impacts and other cost-of-living pressures.

Pricing pollution upstream avoids facility-by-facility compliance, minimises administrative burden, and lets firms respond in the lowest-cost way available. Applied at the point of extraction, a polluter-pays levy would be paid by only around 60 Australian fossil fuel producers, plus importers, yet would cover 80 per cent of Australia’s emissions.

Second, the fair-share levy is a Norway-style tax on gas sales to ensure Australians get a fair return on their own resources. It would increase the effective tax rate on gas exports to 58 per cent, and raise billions that can be used to strengthen the economy, invest in future industries and jobs, and support social services such as health, housing and education. This approach targets economic rents rather than productive activity, preserving investment incentives while ensuring Australians receive a fair return.

Redbridge’s qualitative research shows that these policies attract overwhelming support. 87 per cent of voters agree that the public deserves a better return from the sale of our gas resources. Support for a levy on large polluters commands 68 per cent support, uniting voters across party lines.

These numbers point to a firm position in today’s voter expectations. And as Gen Z and Millennial voters reshape our democracy, it’s reasonable to assume that the popularity of these policy positions will only increase.

Together, these two reforms would cut emissions materially within the next decade while raising substantial revenue, allowing households to be generously compensated for energy price impacts and freeing government to invest in productivity-enhancing priorities rather than relying on higher personal, corporate and other taxes.

In today’s Australia, fairness and cost-of-living relief are not optional add-ons to climate policy; they are the conditions that make reform durable. Any serious transition strategy must reflect that reality, or it will fail.

Baethan Mullen

Chief Executive Officer

Baethan Mullen has over 20 years of experience in public policy, economics and advocacy. Prior to joining the Superpower Institute, Baethan was General Manager of Economics & International at the ACCC, and led the largest energy efficiency program in Australia as Executive Director at the Essential Services Commission.

Ingrid Burfurd

Carbon Pricing and Policy Lead