The following is a transcription of spoken remarks by Professor Ross Garnaut AC at the WEF/First Movers Coalition Green Iron Summit in Adelaide on 20 August 2025.

The text has been lightly edited for clarity.

Thank you. It’s very good to be here. I’ll begin by reminding us why we’re doing these things – talking about green iron and decarbonisation.

The world, human civilisation, faces a dreadful challenge and time is running out. Increasing global temperatures as a result of increases in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere are already doing great damage. Nowhere in the developed world are they doing more damage than in Australia. And here in South Australia, we’re very familiar with the range of challenges.

That’s now with an average global temperature increase from pre-industrial activities of just below one and a half degrees on average. That increase in temperature will keep getting higher and higher until we’ve got net zero. If we get to net zero in 2050, it will stabilise temperatures higher than they are now. The damage that we’re already experiencing now will be greater, but it won’t keep on getting greater after we get to net zero.

If we’re late – if it’s 2060 for the world as a whole, a world that includes India and Nigeria – if we’re late in getting there by 2050, the temperature at which it will stabilise will be higher still. If it’s 2070, it will be higher still. If we never quite get there, if there’s 10 per cent of emissions we don’t get rid of, it will get higher and higher and higher, and the damage will get greater and greater.

It is real, existing damage now. It will keep on getting worse until we get to net zero. It will be better if we could get to net zero at 2035 than 2050. It will be more and more damaging with every slippage that we get.

That’s why we’re doing it. At The Superpower Institute, an independent philanthropic organisation that some of my colleagues here today worked together to establish a couple of years ago – Rod Sims, an eminent Australian, as chair – at The Superpower Institute we’re looking at one particular dimension of the Australian and global transition, and that is what Australia can do through expanding its own zero-emissions industries to supply countries which are not as well endowed as us with zero-carbon opportunities.

Already we’ve put out a number of major contributions, excellent pieces of work. Most importantly, in November last year, The Superpower Institute published a paper released in Parliament House by the now Minister for Industry, who was then Assistant Minister for Future Made in Australia. That looked very carefully at what the world economy will look like when it has net zero emissions.

It will be different in many ways from today. Today the largest trade in the world is the old energy trade – trade in oil and gas and coal. In some years, when the price of oil is particularly high, it has been half of the value of total world trade. That trade has allowed countries with almost no endowments of oil or coal or gas to be great industrial countries – countries in our own region, Japan and Korea, are extreme examples of that.

In the zero-emissions world we’re also going to need very high levels of international trade, but it will look very different. It will not be the same countries which were endowed with large quantities of oil, gas and coal resources that are the big exporters. It will be the countries that are endowed with zero-emissions energy resources, renewable energy. Australia is the standout in the world. There will be special advantages if countries with rich renewable energy also have endowments of the raw materials that need energy for processing. Australia stands out as by far the world’s biggest exporter of minerals that require a lot of energy in processing. We have other advantages as well.

What the New Energy Trade paper says is that if economics drives the reshaping of the world economy, we will see a huge expansion of processed product exports from Australia – goods exports which will remove about 10 per cent of global emissions. And it will not be export of electricity or hydrogen, though there’ll be some of that. It will be mainly export of goods embodying zero-emissions energy or biocarbon, usually a combination of the two. Transport fuels are a combination of the two.

Australian exports will make it possible for countries that have great industrial strength, high incomes, but very poor renewable energy resources of their own to remain countries with high standards of living for their people and high industrial capacity – just as it makes it possible for Japan and Korea today, with no coal or oil resources, to be great industrial states.

That’s what’s at stake. This can be transformational for the Australian economy. We will lose gradually two of our three biggest export industries as the world moves to net zero. We won’t be exporting much gas at all once the world gets to net zero. We won’t be exporting much coal at all when the world gets to net zero. But we will have other opportunities – The Superpower Institute’s paper says several times as large as the industries that we lose.

That’s transformation for Australia. It makes it possible for countries, most importantly in Northeast Asia – Korea, the economy of Taiwan, and to some extent also China and Europe – countries with, relative to their industrial size, small capacity for renewable energy production of their own, to maintain high living standards in the zero-emissions world economy. Australia’s exports can replace about 10 per cent of global emissions. That’s more important than Europe going from where it is now to zero emissions. It’s almost as important as the United States going to zero emissions.

Australia’s exports can replace about 10 per cent of global emissions. That’s more important than Europe going from where it is now to zero emissions. It’s almost as important as the United States going to zero emissions.

That’s what’s at stake.Now the second big paper on our topic is A Green Iron Plan for Australia, which came out a few months ago, last April, launched by Andrew Leigh, the Minister for Productivity and Competition. It digs down into the iron sector in particular.

Iron is one of the two big Australian export sectors, if economics drives the zero-carbon economy. The other one being zero-carbon transport fuels.

The reasons why Australia needs to take this green iron opportunity seriously: first of all, it’s economically tremendously important. Turning our iron ore into iron metal would remove about 4 per cent of global emissions – about four times as many emissions as total Australian emissions at the moment, getting on towards the total emissions from the European community, just from green iron.

It’s also a natural hedge against the loss of our coal and gas exports. There are still some people – not very many people who can read these days – who don’t accept the science of climate change, who recognise we’re in deep trouble already, and getting more seriously in trouble with every year in which we’ve got positive net emissions. But there are lots of people who think, “Well, we’re not going to get there. We’ll just have to live with a destabilised world, a destabilised political order.”

If you think that, then if you invest now in industries that could produce zero-carbon exports from Australia, you won’t do very well. But you might be wrong. Humanity may succeed in dealing with this destabilising problem of climate change. If you think that’s a possibility, you should want to hedge against it. Investing in the green industries is a natural hedge against the – what I would say is likely, some would say possible – loss of our coal and gas industries.

It’s using green hydrogen in industry, not as an export product in itself, that’s going to be important in Australia. We got this a bit wrong when the Commonwealth Government – the Morrison Government – made a big fuss about a hydrogen strategy. Alan Finkel was Chief Scientist. They were right that hydrogen was going to be important. But there are all sorts of reasons why it’s going to be much less important as a direct export in liquefied form, or even embodied in products like ammonia.

This was set out in my first Superpower books. I explained there in some detail why hydrogen itself would not be a big export. It’s the smallest molecule – it seeps out between the molecules of standard steel. It’s expensive to build materials that will capture it. You lose some on the journey. And it’s a dangerous greenhouse gas in itself as you lose it without combustion. It won’t liquefy until you get almost to absolute zero. You lose almost half of the energy just in getting it into a liquid form so you can transport it. Very different from methane, from so-called natural gas.

So, hard to export in that form. Very easy to export if embodied in iron – if it’s used to convert iron ore into iron metal. Very easy to export if it’s used with biocarbon to make zero-carbon transport fuels.

This report looked very closely at the costs of green iron in different parts of Australia. We looked at what we thought were the five leading candidates. We’re talking about the early stages of development, the early projects. The very lowest cost happens to be in South Australia – the Upper Spencer Gulf. Their advantages include the juxtaposition of magnetite resources with exceptional renewable energy resources, but also the established infrastructure, and the fact that South Australia is a nearly 100 per cent renewable energy grid – soon to be 100 per cent. You’ve got high variability of prices. Hydrogen production is highly variable. You can greatly reduce the cost of iron-making by only using the electricity and the electrolyser when renewable energy is abundant and cheap. That reduces the overall cost. The detail of this is in the report, so I’ll just go quickly through it.

We won’t get to net zero without quite strong government policies. It’s one thing to agree we have to get there, but we won’t get there without strong policies.

There are three policies that The Superpower Institute emphasises in this report:

Standard economics – taught in every university course in the world, I think – says that markets don’t work in the public interest if there are external costs from private activity that are not either blocked by regulation or balanced by a tax on that activity.

The extreme radicals of right-wing fundamentalism who said markets should do everything and governments nothing – people like Friedman and von Hayek – said you do have to correct for market failure by taxing external costs.

There was a time in the early development of industry – not a lot of industry along the Torrens, but in Melbourne along the Yarra, or Perth along the Swan River – when industry just dumped all of its rubbish in the river. That was the cheapest way of getting rid of rubbish. The cheapest way of making vinegar or starch, that’s for sure – by dumping the waste in the river.

The cheapest way of making iron is if you produce a lot of carbon dioxide waste, which damages every other human on Earth, the cheapest way of getting rid of it is to throw it into the atmosphere and let it damage the climate. No doubt that’s in the private interest of any producer of iron. But good economics says, in the elementary textbooks, that when any firm or individual is damaging others by their economic decisions, they should either be stopped from doing that by regulation or they should pay a tax equal to the damage they do.

We need to price emissions. Professor Stern at the London School of Economics called untaxed emissions ‘the greatest market failure in human history’.

The second requirement for government is providing common-use infrastructure and public goods infrastructure: electricity transmission, hydrogen storage and transport, particularly important.

The third is the positive external effects of innovation. Just as if you’re emitting greenhouse gases you’re damaging everyone else and should be taxed, if you’re pioneering a new technology you’re generating knowledge that everyone benefits from. The efficient operation of markets requires governments to support that fiscally. The innovation – the early use of new ways of doing things should be subsidised. That’s just good economics. That’s not a subsidy; not doing it is to subsidise everything else.

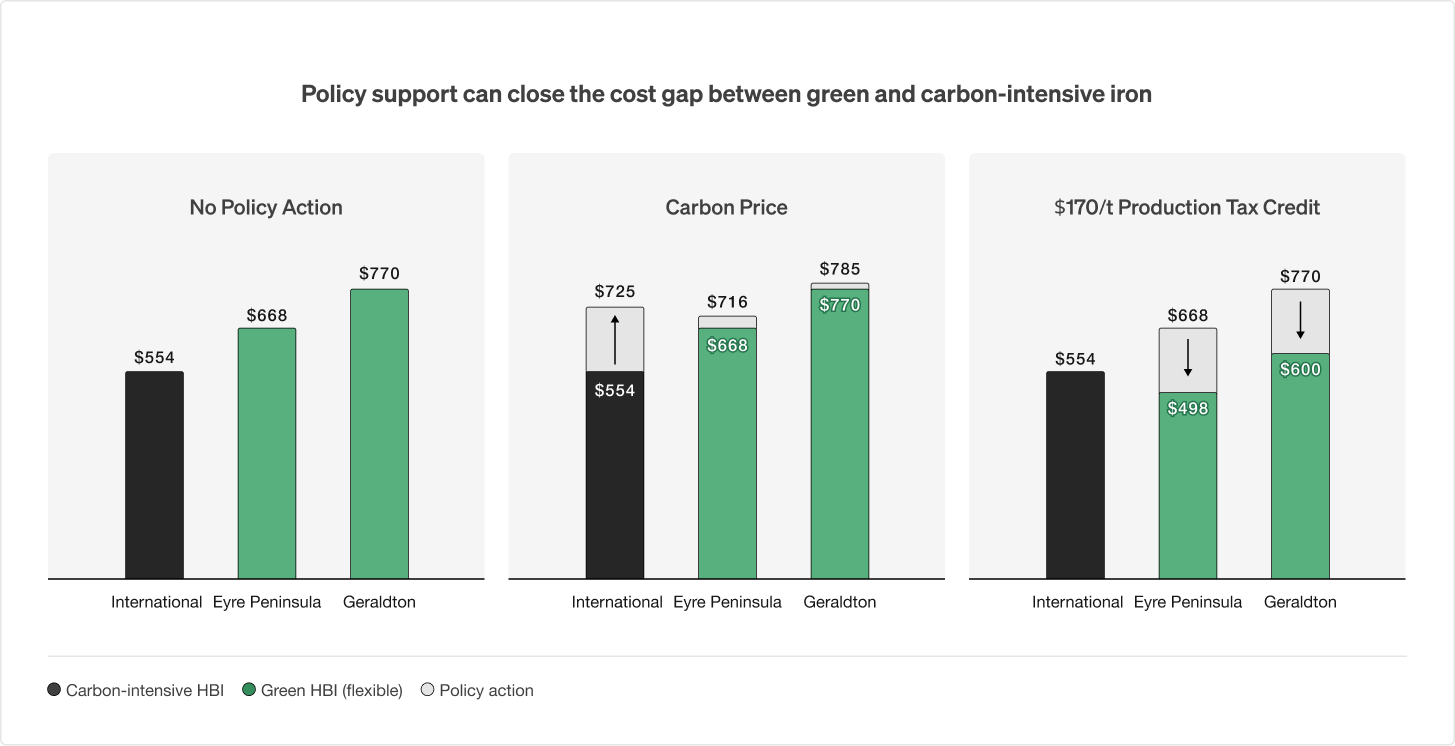

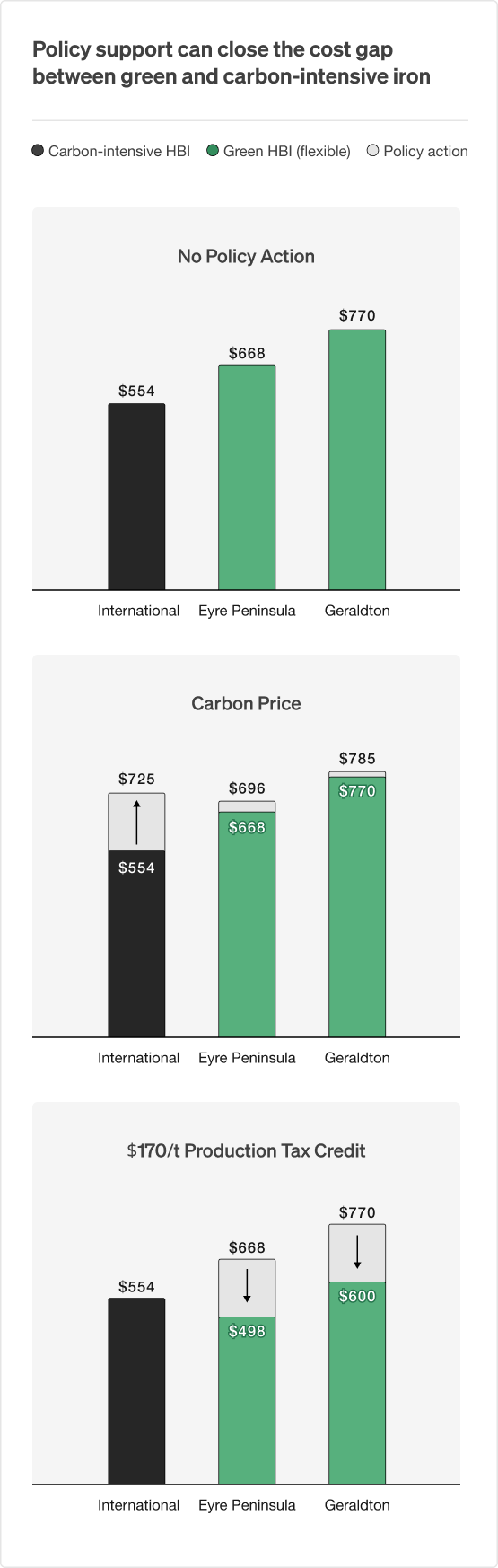

In this chart – it will be too brief to absorb it properly, but it’s in The Superpower Institute’s report on green iron on the website – with a production tax credit, you start to get very close to international current prices for brown iron made from gas or coal. In particular, in the Eyre Peninsula you’re getting globally competitive, but only if recognition of the external costs of greenhouse gas emissions is taken into account.

This is a bit more complex – you’ll have to study the report to absorb this – but we’re also taking into account here a reasonable assessment of the benefits that the first movers in the new technologies provide to others. We suggest a general capital grant of about 30 per cent of the capital cost would handle that external benefit from innovation.

The Minister referred to the billion-dollar Iron Innovation Fund for the first movers – half a billion each for the first two. That’s about 30 per cent of $1.5 billion, which is about the capital cost of a one-million-tonne plant. So that aspect of the government’s policy has got it about right. But there will need to be many different kinds of innovation, and we’ll need to have fiscal support for many different variations on that innovation scheme. The Minister’s $1 billion will have to be extended.

Again focusing on this region in South Australia. The big iron ore region in Australia is the Pilbara. The second biggest iron ore region is the Eyre Peninsula and Upper Spencer Gulf, and the Midwest of Western Australia, the Geraldton region, the third. The costs of building things are not as high as in the Pilbara and in remote areas of Australia. It’s adjacent to high-grade, suitable magnetite resources. Very good capacity factors for wind and solar. The combination of wind and solar, especially if the wind is diurnal – blowing more strongly at night – is a big advantage. Interacting with the grid is a big advantage. And the fact you’ve got established industrial regions there is a good start.

So, South Australia is green iron-ready now, with economically rational policies – production credits equivalent to what a carbon price would do if we had a carbon price, and support for innovation. That makes the Upper Spencer Gulf economic now. If those policies are properly in place, then we can have production by 2030.

Initially, one of the advantages is you’ve got existing transmission infrastructure, so you can move quickly. That would support about one million tonnes of production in each of the industrial centres of the region – Port Pirie, Port Augusta, Whyalla. If you get much bigger than that, you need more investment and it will take longer. But you could have three-million tonne-plants by 2030.

This could be part of the Whyalla solution. Whyalla – a beautiful plant, a brilliant idea of a great Australian, Essington Lewis, in 1941, to build a blast furnace and associated steel mill there. Maybe that same steel mill, as it was in 1941, is not the best use of those resources in 2025. The work that we’ve done shows that a green iron solution supporting an electric arc furnace and downstream processing would be more competitive. But Essington Lewis was a great man with great ideas, and there’s still some support for continuation of his ideas from that time.

But quite separately from the future of Whyalla, the big future of the Upper Spencer Gulf is green iron. There will be multiple plants in each of the Upper Spencer Gulf cities. Each of them will employ a lot more people, together with the renewable energy supply chains that support them, than the steel industry supports in Whyalla today. That will happen if economics drives the future.

Ross Garnaut

Director

Ross Garnaut AC is a renowned economist specialising in development, economic policy and international relations. He is Professor Emeritus at the University of Melbourne and a Fellow of the Australian Academy of Sciences. His contributions to trade policy and climate change have made him a trusted adviser to successive Australian governments.