There's a growing and credible economic theory that Australia has the sun, the wind, the minerals and the space to become an economic superpower in a world moving to net zero.

But seizing that future, its advocates argue, would mean rewriting the way our economy works, and reimagining our place in the world.

Is it really possible? And if so, do we have the will to do it?

TRANSCRIPT:

Peter Martin:

On the face of it, Australia’s luck is set to run out as the world moves to net zero. We’re among the biggest exporters of coal and gas, but there’s something else we could export. Something we’d be much better at making, in large quantities, than just about every country on Earth.

It’s green iron and green aluminium, and a lot of other green products manufactured here, using our near-unique blend of sunlight, wind, minerals, and acres and acres of space.

Getting there wouldn’t be cheap. We’d need to make unheard-of amounts of electricity, and we’d need to upend our economy.

We’d need to become an economic superpower. Could we? Is this the sort of Australia we’d choose, if we could choose our own Australia?

And are we even up for it?

Welcome to Choose Your Own Australia, a special three-part series from The Economy, Stupid on ABC Radio National with me, Peter Martin, and my very special guests, two people who know an awful lot about the superpower opportunity and whether or not it might fall from our grasp.

Ingrid Burfurd is the Carbon Pricing and Policy Lead at the Superpower Institute. She’ll tell us about the Institute in a moment. And Ben Potter, who’s contributing editor at The Energy, a new news site about energy.

Welcome, Ingrid, and welcome back, Ben.

Ingrid Burfurd:

Thank you, Peter. It’s an absolute pleasure to be here.

Ben Potter:

Great to be back, Peter.

Peter Martin:Ingrid, tell us first, what is the Superpower Institute? Where did it come from?

Ingrid Burfurd:

We’re a relatively new think tank. We were established in 2023 by the economists Ross Garnaut and Rod Sims.

Peter Martin:

People have heard of them. They’re quite famous, right?

Ingrid Burfurd:

They are. They are. It’s a privilege to be working with them and all my other colleagues.

And we were established with a single purpose, and that’s to help Australia seize the extraordinary economic opportunities that will be created as the world decarbonises and then later as it becomes a post-carbon economy.

Peter Martin:

So you’re a bit like evangelists and also enablers, working out how we can do it. Tell us about the vision. Where does it begin?

I’m guessing it begins with the world committing to net zero. Now, what follows from that?

Ingrid Burfurd:

You guessed correctly. It does begin with the expectation that the world will reach net-zero carbon emissions. As the world decarbonises, it’s going to need to electrify things.

So at the household level, that means driving EVs instead of petrol cars. But it also has to happen for industries. And so that means that industries that currently use metallurgical coal and thermal coal and gas to produce these incredibly energy-intensive products are going to need to, as much as possible, electrify.

And that’s going to massively increase countries’ demand for electricity. So for our trading partners, like Korea and Japan, that’s sort of in the vicinity of about three times an increase in their electricity demand. For China, it’s four times.

And for India, it’s even larger, up at about twelve times. And then, of course, there’s this question of whether those countries can meet that demand. And the answer is that even China, which has actually quite good renewables by most international standards and a reasonably ambitious nuclear build-out pattern, even China will not be able to.

And so what will happen is that these countries will need to find a way to meet their electricity demand. And that’s where Australia steps in as a superpower, because we have this extraordinary capacity to generate renewable energy. We have this vast landmass and we have a very small population.

So our domestic demand is very small. And that’s what helps to keep that price down.

Peter Martin:

Where would it be? I ask this because I think I’ve seen a map which has the world’s solar resources, if you like, good sun, the world’s wind resources mapped on them. A lot of them are in Australia, plus space.

Where would these installations be?

Ingrid Burfurd:

So we have remarkable solar and wind at many locations around Australia. What would you expect to see happen is that we’d see these superpower export industries emerge in hubs, where there’s a combination of that extraordinary solar and wind, but also access to ports and access to minerals and renewable carbon either locally or through those ports.

And those locations are places like the Eyre Peninsula in South Australia, Oakajee, which is in the mid-west of WA, and Barkly in central Queensland, but you can access that through the port at Gladstone.

Peter Martin:

Ben, the vision is that we’re uniquely positioned. Are we the only country that can do this? Surely we shouldn’t be, in the words of Kylie Minogue, so lucky.

Ben Potter:

Peter, the answer is emphatically no, we’re not the only country that wants to do it or can do it. Although we have the unique advantages that you and Ingrid have outlined.

One thing we’ve lacked is an economy-wide carbon price. Europe has that, and I think as a consequence of that, a company in Sweden called Stegra is planning to commission the first commercial green iron plant. This is a direct-reduction iron electric arc furnace plant using green hydrogen by the end of next year. So that’s in less than 18 months if they stick to their plans.

And then there are those sun-drenched petro-states around the Gulf of Arabia. Those countries are redirecting their petroleum billions of dollars into green energy developments, I think, as a hedge, but also to take advantage of their own solar resources.

So it’s something of a race.

Peter Martin:

What’s the upper limit to the opportunity for Australia, as you and the Superpower Institute see it, Ingrid? How much of the world’s iron could we conceivably make? How much of the world’s aluminium, aviation fuel and other things?

Ingrid Burfurd:

At the moment, Australia produces about 40% of the world’s iron ore and about 30% of its bauxite. So what we could do is to process that here and to move up the value chain and turn that into 40% of the world’s green iron and 30% of the world’s green aluminium.

Peter Martin:

We could make 40% of the world’s iron.

Ingrid Burfurd:

Not just iron, Peter, but green iron.

Peter Martin:

Well, all of the world’s iron, I assume, would be green by then. What else could we make and in what sort of quantities?

Ingrid Burfurd:

We think Australia has the combination of location and resources and strong trade relationships that mean we could make up to a quarter of the world’s green silicon and polysilicon, which we hear about a lot at the moment, but also green ammonia and urea, industrial methanol, and those long-distance fuels that we’re going to need for shipping and aviation and long-distance trucking.

Peter Martin:

If we did that, what could it do to the world’s emissions? Now, if we cut our own emissions, we can’t do that much. We’re about 1% of the world’s emissions, a third of 1% of the world’s population.

What sort of contribution could we make?

Ingrid Burfurd:

So work by my colleague, Reuben Finighan, suggests that we could contribute to reductions worth between 7% and 10% of the global total by 2060, which is a pretty remarkable achievement.

Peter Martin:

Little Australia, by itself, if we make this much, if we win the race, if we make this much of the world’s green iron, green aluminium and other things, we could displace 7% to 10% of the world’s emissions.

Ingrid Burfurd:

Yeah, that’s right. And the reason those numbers are so big is that it’s important to remember that the industries we’re talking about are incredibly energy-intensive. And so at the moment, we’re making those really energy-intensive goods with fossil fuels.

So just to take an example, if you think about a tonne of steel at the moment, that includes about 2.2 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions. And so if you replace that steel with green iron and green steel, you’re displacing nearly all of those emissions with a product that produces hardly any.

So as you bring those green products online, you’re doing a huge amount of lifting to displace that really carbon-intensive production that we have at the moment.

Peter Martin:

What’s the size of the financial benefit to Australia? What could we earn? And how would it compare with what we earn at the moment from exporting coal and gas?

Ingrid Burfurd:

Based on the numbers I outlined earlier, we think that these industries could be worth up to a trillion dollars by 2060.

Peter Martin:

That’s per year.

Ingrid Burfurd:

Per year.

Peter Martin:

One trillion dollars.

Ingrid Burfurd:

That’s correct. It’s a very big number. Coal and gas are worth about $120 billion a year at the moment in export revenues to Australia.

So they’re two out of our three top exports. And so what we’re aiming to do is, as they come down through time, to replace those with revenues from the green superpower exports, which are worth potentially eight times more by 2060.

Peter Martin:

Ben, would all this be easy? Let’s talk about land. We’d need to use 1% of our land for electricity, which is actually quite a lot. We’d need to use 5% of it, according to the Superpower Institute, for biomass. That’s also a lot.

You’ve spent a lot of time covering the resistance of farmers and others to simple things, like stringing up transmission lines. There’s also native title.

Would this sort of thing be at all easy in Australia, as we know it?

Ben Potter:

None of it’s going to be easy, Peter. And the land question is one of the most difficult challenges of the whole vision.

I’ve visited farmers within a few hours’ drive of Melbourne who are particularly up in arms about major transmission projects involving 70-metre-high towers running through their land.

But I think the loudest voices may not be the majority. Farmers are going to be challenged by climate change and extreme weather, probably one of the most challenged industries.

So I retain the hope that over time, the appeal of reliable income from biomass production and wind and solar farms and poles and wires will become more compelling.

There’s also a growing agrivoltaic movement in Europe and the US. I think it’s got a toehold in Australia, but we’re a little bit behind.

Peter Martin:

What’s agrivoltaic?

Ben Potter:

Agrovoltaics is the combination of solar panels and livestock grazing in a field. It’s been found that animals like shade, just like we do, and they actually thrive in that environment.

And the grass grows under the panels. I’ve seen the videos. It looks wonderful.

Ingrid Burfurd:

Thank you for equipping me with a new term there. I hadn’t heard of agrivoltaics before, but I’m delighted that I have.

Peter Martin:

Ingrid, for electricity, you say we’d need to make about 9,000 terawatt-hours. Right now, we make 200. Where would we get the workers, particularly in these locations, which are not places where people normally live?

Ingrid Burfurd:

One of the things about the Australian workforce is that it’s incredibly skilled and highly mobile. We know that because it’s the backbone of our mining and resource industries.

That doesn’t mean we’re perfectly set up for the scale of renewable investments that we’re going to need. They’ll be on a scale that we haven’t tried to navigate before.

If we don’t plan for that, we’ll have workforce shortages and material bottlenecks, which will slow down installation and push up prices. So the best way to manage those challenges is to anticipate them.

We need a really strong policy signal about what’s around the corner, ideally as part of a green export industry strategy.

Peter Martin:

Let’s turn to the fruits of success. Ben, I’m wondering how our economy would cope. If we get all of this income, it would force up the value of the Australian dollar. It would make our buying power huge, but it would make just about every other industry uncompetitive.

Would we be the Saudi Arabia of the late 21st century? Would we even be open to buying almost everything from overseas?

Ben Potter:

Peter, it’s a bit premature to be answering this classic economist question on the so-called Dutch disease.

Before we get there, we’d need to realise the green energy superpower vision, and that would be a historically colossal achievement, greater than the 1950s expansion of industry and manufacturing.

It would be a good problem to have, but it would require careful thought and planning, redistributive tax policies, perhaps even a super-profits tax of some kind.

We already purchase most of our non-food and beverage consumer goods from overseas, so that dimension of the problem may not be a huge step.

But there’s a huge amount to achieve before we have to grapple with that problem.

Peter Martin:

Have you grappled with it at the Superpower Institute, Ingrid? It seems to me like an economy that does nothing other than these industries and the industries that support them.

Ingrid Burfurd:

We’ve certainly given it a lot of thought. We’ve been modelling what the superpower might look like out to the middle of the century. And as Ben has pointed out, those booming exports will drive up the Australian dollar, drive up our terms of trade, and make it harder for other export industries to compete.

We experienced that during the mining boom. In 2010, the Australian dollar hit parity with the US dollar. It was wonderful. We could buy anything at US prices.

But trade makes us collectively better off, while making some people worse off. For social cohesion, it’s crucial that we use that shared wealth to benefit all Australians.

We can’t be anti-trade.

Peter Martin:

What about the rest of the world, Ben? If the world moves away from free trade and doesn’t want to buy from Australia, the vision’s in trouble, right?

Ben Potter:

It’s a challenge, Peter. Free markets aren’t the zeitgeist in the era of China–US rivalry.

Hugh McKay points out that China has invested heavily in blast furnace steelmaking and won’t abandon those assets quickly. It will pursue green pathways that preserve those investments.

Even so, comparative advantage still matters. Even if we only get halfway to the Superpower Institute’s vision, it would still be a massive boost to exports and prosperity.

Peter Martin:

Ingrid, another roadblock might be the world not decarbonising at all.

Ingrid Burfurd:

There are three futures. One where the world doesn’t decarbonise. One where it does and Australia prospers. One where it does and Australia misses out.

If the world doesn’t decarbonise, the costs are astronomical. Any stranded assets would be trivial by comparison. We should not plan for that world.

So the real question is whether we plan properly for a decarbonising world. And we can’t wait.

Peter Martin:

How do we get there?

Ingrid Burfurd:

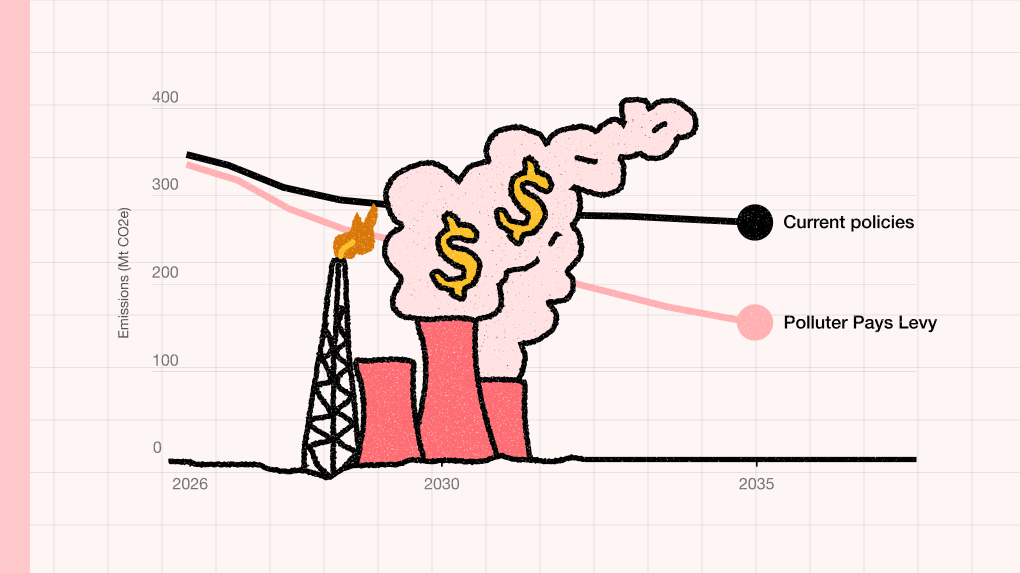

Carbon pricing is spreading globally. China, Japan, Europe. Border carbon adjustments will strengthen demand for green exports.

On the supply side, we need faster approvals, policy certainty, and targeted support to bridge the green premium, such as production tax credits for green iron.

We also need innovation support. These are first-of-a-kind projects.

Peter Martin:

Ben, does handing out grants worry you?

Ben Potter:

There are risks, but Australia has become quite good at managing them. CEFC and ARENA have strong track records.

Some losses are inevitable. But people forget that the US loans program backed Tesla as well as Solyndra.

Given the scale of the opportunity, some losses aren’t a big problem.

Peter Martin:

If Australia’s advantage is so clear, why does government support matter at all?

Ingrid Burfurd:

Because it’s about readiness. Whether we’ve done the hard work of innovation and shared infrastructure so private investment can follow.

Peter Martin:

Ben, are we even up for this? Are we still bold?

Ben Potter:

The real question is whether we want to be poor. Coal and gas will go. The only question is how quickly.

We have no choice. The question is how fully we embrace the opportunity.

Peter Martin:

Ingrid, I think you’ve convinced Ben.

Ingrid Burfurd:

We have a single goal at the Superpower Institute. But achieving it is a transformation.

Australia’s been through transitions before. They seem hard until you’re in them.

Peter Martin:

I’m meant to be sceptical. I’m fighting it. But I’m becoming excited.

Ingrid Burfurd, Policy Lead at the Superpower Institute, and Ben Potter, Contributing Editor at The Energy. Thank you both.

Ingrid Burfurd:

Thank you so much for having me.

Ben Potter:

A pleasure to be on the podcast, Peter.

Ingrid Burfurd

Carbon Pricing and Policy Lead