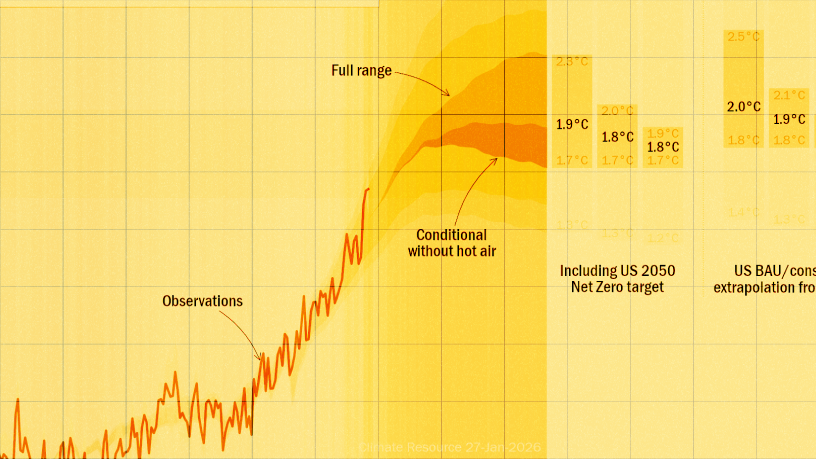

What should we make of last Thursday’s announcement of Australia’s target for emission reduction, and the released pathways to achieve this? We can be broadly comfortable with the upper level of the target, the pathways largely have merit but also some flaws, but without significant policy change we will not see our emissions in the target range by 2035.

The Government is correct that to be worth setting, targets must be both ambitious and credible.

The Government’s 62-70% target, at the upper end, with some generous assumptions, can be seen as Australia doing its fair share to keep world emissions consistent with constraining warming to well less than two degrees. And for a country committed to this objective it is necessary that we are seen to play our part.The stance of Mr Trump makes this more important, not less.

The government’s pathways to achieve this describe fairly well what needs to be done technically to reduce emissions, and the technology is available. Expanding the role of electrification powered by firmed renewables, accelerating the deployment of new green technologies, using zero emission fuels, for example, are all sensible and doable. Concerns arise, however, when there is considerable reliance on carbon capture and storage, which usually only makes sense when used to get more gas or oil out of an aging reservoir. And there will be continuing reliance on firms buying Australian Carbon Credit Unit’s (ACCU’s) created through land use change but without enough being done to ensure their integrity.

There are, however, two major problems.

First, while we can see what companies need to do to decarbonise, we cannot see why they will do this. Companies are already producing products and services in ways that maximise their profits. What will make them change what they have found to be profit maximising?

The Government can encourage companies to decarbonise through its own funding, but Australia’s continuing budget deficits will limit what the Government can fund. And action will be government led, not market driven, which cannot unleash the innovation and range of activity we need.

It is important to note that outside of the land use sector Australia’s emissions have broadly remained flat since 2005. Continuing with the current types of policies is unlikely to change this.

After Thursday’s announcements the Government continues to rely on two main policies to achieve its targets. The Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS) sees government underwrite renewable energy generation and storage projects.Not only does the government, not the market, decide which generation projects proceed, but the underwriting carries a very large contingent liability for an already under pressure budget.

For industry we have the Safeguard Mechanism which requires large industrial facilities to reduce their emissions by a set percentage each year. This covers less than 30% of the economy, although the Government is talking about increasing this; but it is based on emission intensity and so extra production will see emissions rise.

The second related problem is that there is a cost to our transition and currently the burden largely falls on consumers and taxpayers, not emitters. This is not only inequitable; it will severely constrain our emission reduction progress as there is a limit to voter tolerance, and to our budget capacity

There were always going to be costs from the transition: higher electricity prices as we subsidise renewable energy production and prematurely replace existing fossil fuel plant, although an important part of the electricity price rises we are currently seeing are from higher gas prices; companies under the Safeguard Mechanism who use fossil fuels to make cement, glass, fertiliser, plastics and chemicals must spend to decrease emissions or buy ACCUs, and when they can they will pass these costs on; tighter vehicle standards must increase prices a bit no matter how desirable this move is; and there is a large budget spend which must be funded by us all with higher taxes or reduced other services.

So who pays? The equitable approach is “polluter pays”. Indeed, this addresses completely and uniquely both of the problems that will otherwise undermine our transition.

So who pays? The equitable approach is “polluter pays”.

If Australia is to achieve a credible emissions reduction target, we need to energise the private sector by providing the appropriate incentives for emission reduction. This requires a price on carbon so that those using fossil fuel pay for the damage their products do to the environment and the government gains necessary funding to remove the effect of the transition on consumers and the budget.

Some argue that a price on carbon means higher electricity prices faced by consumers. They are incorrect. With the green premium achieved by the carbon price there will be more renewable electricity generation and so eventually lower electricity prices; there will be money raised by the carbon price to more than fully compensate households for the immediate price effects of the transition; the Commonwealth budget position will improve; and higher productivity will result as high cost and somewhat arbitrary interventions are no longer needed.

If we want to reduce emissions to meet our targets we must make emitters pay. While putting a price on carbon is not all we need to do, it is a necessary component of any plan to significantly reduce our emissions.

Rod Sims

Chair, The Superpower Institute

Rod Sims is Enterprise Professor at the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Melbourne, and Chair of The Superpower Institute. He previously chaired the ACCC (2011-2022), served as Deputy Secretary (Economic) in the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, and Principal Economic Adviser to PM Bob Hawke (1988-1990).