With the political turmoil and the Liberal leadership settled for now, energy and climate issues will surface again. You will hear, for example, that a focus on net zero is the cause of Australia’s high electricity prices, which is not true. Underpinning all this will be statements that the world is moving away from addressing climate change, US President Donald Trump has taken the US out of the Paris Agreement and is now encouraging higher emissions, so why should Australia bother?Further, you will hear that COP30 was a failure, world emissions are rising, and Australia is doing way more to reduce emissions than others.

The reality is very different. The growth in world emissions has fallen progressively over recent years and, on current trends, they will soon start declining. Likewise, fossil fuel production. And while the world is not currently on track to have temperatures rise by no more than 1.5 degrees, the outlook has improved considerably since the Paris Agreement was adopted 10 years ago.

The growth in world emissions has fallen progressively over recent years and, on current trends, they will soon start declining.

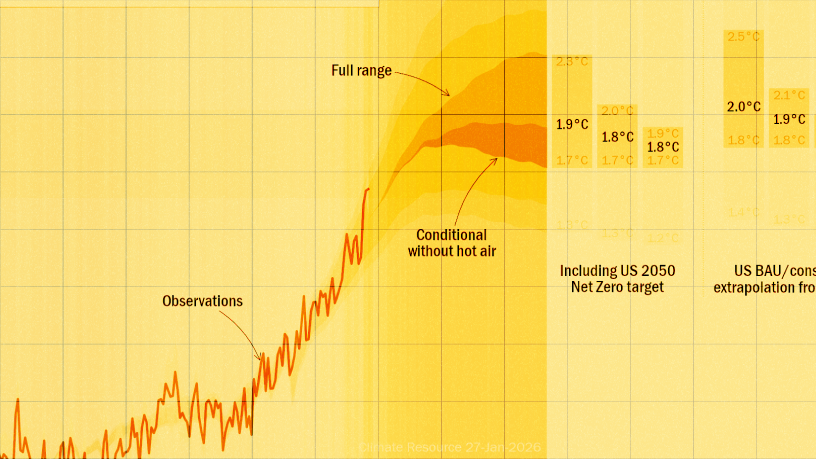

In 2015, the world was on a disastrous track to see temperatures rise by around 4 degrees above pre-industrial levels. If you ignore commitments and simply take current emission trends forward, the world is currently on track to see temperatures rise by 2.5-2.9 degrees. When you add commitments already made by countries, the world is now on track to limit warming to around 1.8-2.2 degrees. To be clear, the world is a long way from where it should be, but progress is being made.

The increases in coal, gas and oil production over the last 25 years have slowed significantly. Coal consumption, for example, has grown at less than 1 per cent a year on average since 2015, in contrast to growth of well over 4 per cent a year in the previous decade. It is also worth looking below the headline figures. China, India and Indonesia were responsible for 73 per cent of global consumption of coal in 2024; from 2015-2024 coal consumption in the rest of the world declined by 23 per cent.

China has embraced renewable electricity in a stunning way. In 2024, more than 80 per cent of China’s new electricity generation was from clean energy, led by wind and solar. As a result, China’s power-sector emissions are falling, and China’s output from coal and gas-fired generation fell by 1.9 per cent in 2025. Further, China’s overall carbon dioxide emissions have now been flat or falling for 21 months, starting in March 2024.

In 2025, India met a key 2030 target – to have 50 per cent of installed electric power capacity from non-fossil fuel sources – five years earlier than the deadline, and its emissions from fossil fuel electricity generation will also soon peak.

Trump has taken the US from the Paris Agreement and last week announced the reversal of the Biden era “endangerment finding” that underpins much of US environmental legislation. In essence, many restrictions on US greenhouse gas-producing industries will be removed. The US withdrawal, however, is currently forecast to add 0.1-0.2 degrees to global temperatures, crucially depending on assumptions about what happens in the decade beyond 2035.

These estimates of the impacts on global warming will be updated as the implications become clearer. Market-driven investment, a range of court actions and the role of sub-national governments will lessen the impact of Trump’s actions. More important, investors look to the long term, beyond political timetables, and they will often realise that the pressure to avert the worst outcomes from climate change will not disappear.

The drivers of these changes are not just the need to transition from fossil fuels. Solar and wind are now often competitive with existing fossil fuel powered generation. We know that the cost of solar and wind have plummeted, falling by 80 per cent since 2015. In 2023, spot prices for solar PV modules declined by almost 50 per cent year-on-year, with manufacturing capacity reaching three times 2021 levels. Global lithium-ion battery deployment in 2025 was six times as high as in 2020.

Also driving the change is the need to sell goods into Europe with its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, and the need for energy security.

Across the world, while coal-fired electricity generation still dominates, the carbon intensity of electricity generation is declining. From 2015, it has declined 14 per cent worldwide. China has seen a 23 per cent decline, and India 13 per cent, while the carbon intensity in the US has declined by over 30 per cent and in the EU the decline has been over 50 per cent. Further, the emission intensity of developed world economies has crashed in the last 20 years, falling by between 64-74 per cent in the EU, UK and the USA.What matters, of course, is total greenhouse gas emissions. Since 2005, ignoring land use, the UK has seen reductions of over 40 per cent, the EU over 30 per cent and the US over 15 per cent. Australia over the same period has seen its emissions, excluding land use, fall by around 4 per cent. If you include emission reductions due to changes in land use then Australian emissions have fallen 28 per cent, although there are measurement problems with this figure. Compared with similar economies, Australia still has substantial ground to make up.

The world has an enormous amount to do to avoid the worst effects of climate change, and the risks remain serious. The energy transition is well under way, however, and politicians need to be honest with the public about this.

Co-authored by Climate Resource CEO Rebecca Burdon and TSI Chair Rod Sims.

Rod Sims

Chair, The Superpower Institute

Rod Sims is Enterprise Professor at the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Melbourne, and Chair of The Superpower Institute. He previously chaired the ACCC (2011-2022), served as Deputy Secretary (Economic) in the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, and Principal Economic Adviser to PM Bob Hawke (1988-1990).