Thank you to the Australia Institute for the invitation to join you on the lands of the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people.

Today’s conference focuses on the practical question of how to raise revenue in a way that balances social and environmental priorities with the goal of economic efficiency.

This isn’t always easy.

Revenues mean taxes. But on the social front, plenty of taxes are regressive.

And on the efficiency front, raising revenue usually creates a drag factor on the economy. In econ jargon, taxation has a ‘marginal excess burden,’ with every dollar of revenue that is raised creating distortions that have economic costs.

So everyone should welcome taxes that correct economic distortions, rather than creating them. And everyone should be pleased when taxes help address environmental problems, and raise more than enough revenue to compensate people for higher costs, including and particularly lower-income households.

In other words: there’s a lot to like about putting a price on carbon emissions.

A carbon price tackles three really big policy problems.

Australia needs to decarbonise its economy, and to strengthen its structurally weak budget.

I’m going to discuss the implications of tackling these two problems in the context of a third: Australia’s long-term economic challenges.

But first, decarbonisation.

Decarbonising our economy matters for two reasons.

First, a failure to reach net zero in 2050, along a path of predictable and timely emissions reductions, creates significant threats to Australia’s environment and economy.

These risks have been consistently articulated across a number of reports – most recently Treasury’s Net Zero Modelling, and the National Climate Risk Assessment. Amongst the developed countries, Australia will be particularly badly affected by climate change.

Fortunately we are endowed with abundant renewable energy resources, and can also benefit disproportionately from the trade opportunities created by global decarbonisation.

Which brings us to the second reason we need to decarbonise our economy.

To successfully advocate for the formal agreements and informal relationships that underpin global decarbonisation, Australia needs to reach net zero emissions by 2050, within an emissions budget that is consistent with Australia’s ‘fair share’ and with limiting temperature rises well below 2*C.

These goals have been formalised in the government’s international commitment to reduce emissions between 62 and 70 per cent below 2005 levels, by 2035.

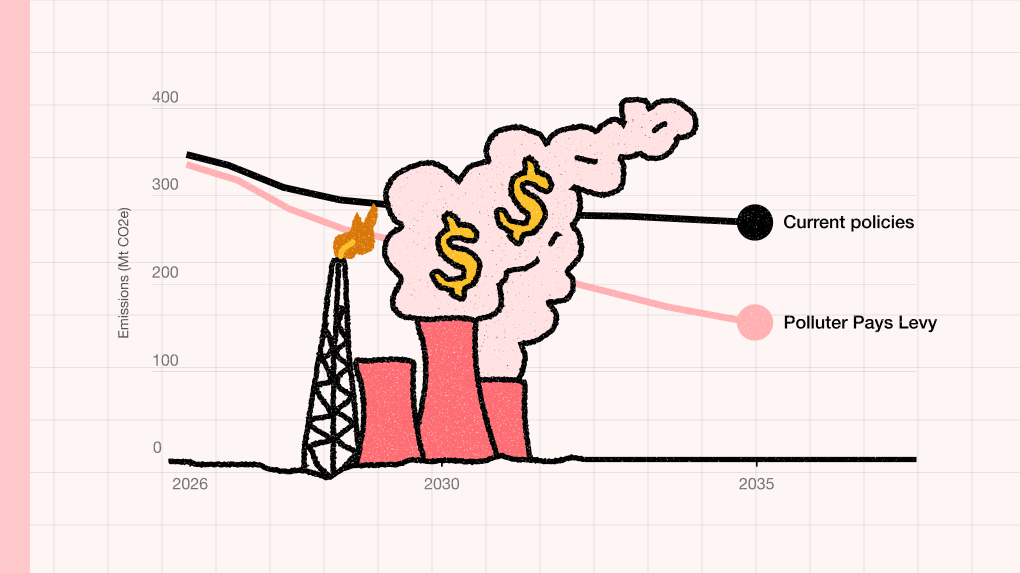

But to reach this target, Australia’s annual rate of emission reductions needs to more than double.

Australia reduced its emissions by 9 mega tonnes each year between 2006 and 2024. It needs to reduce emissions between 19 and 24 mega tonnes each year from now through to 2035.

The upshot is that we need policies that will decarbonise the economy much faster than it has decarbonised over the last two decades.

Unfortunately, though, rapid decarbonisation will be harder against a backdrop of sustained budget deficits. Budget projections do not point to a surplus until 2034-35.

You don’t need to be a fiscal conservative, or an economist, to appreciate the importance of a sustainable budget.

Strong budgets don’t just deliver good credit ratings – they also support investments in a fair, flourishing society, and the environment. The reality is that worthy causes compete for scarce funds, and when funds are thin on the ground, social and environmental programs are vulnerable.

The government therefore needs to raise revenue.

It needs to do this, and to reduce emissions, in the context of long-term economic challenges.

High on the list is Australia’s sustained productivity slump. In the past 10 years, productivity grew by less than a quarter of its 60-year average. Measures of long-term productivity growth have been falling steadily.

Australia also needs to prepare for the loss of fossil fuel revenues. Coal and gas are two of Australia’s top three exports, recently worth about $150 billion per year, and typically about $120 billion a year.

Whatever the short-term effects of Trump’s policies on other countries’ decarbonisation, the science doesn’t change. Even if the pace of decarbonisation is uncertain, the direction is clear.

With the right policies and support, Australia can hedge against these losses by harnessing its comparative advantage in zero-carbon, energy-intensive goods. These green exports can underpin future prosperity.

The government therefore needs to strengthen the budget with taxes that encourage productivity by minimising economic distortions, and use price signals to align investment with the goal of decarbonisation.

New revenues should be substantial enough to provide support for industries where Australia has a long-term comparative advantage, lifting productivity and growth.

Reducing emissions, raising revenue, and strengthening Australia’s economic fundamentals are big challenges.

A carbon price ticks every box.

The concept is pretty simple: put a tax on damaging activities so that polluters pay for the damage they inflict.

We know carbon prices work.

When Australia had a price on carbon between 2012 and 2014, emissions fell significantly.

The price signal created by the tax systematically encouraged lower-emissions sources of power over higher-emissions sources. Black coal power expanded relative to brown coal. Gas power expanded relative to coal. Renewables expanded relative to gas.

ANU research found that: demand in the National Electricity Market declined by nearly 4 per cent; the emissions intensity of electricity dropped by about 4 and a half per cent; and emissions fell by more than 8 per cent compared to the two-year period before the carbon price.

When the tax was repealed, emissions rose.

Since 2014, governments have worked to reduce emissions with second, third and fourth best policy instruments.

Australia has the Safeguard Mechanism to cover our largest polluters outside electricity generation. In the transport sector it has a New Vehicle Efficiency Standard and has tax breaks for electric vehicles. It has renewable energy targets and the Capacity Investment Scheme in the electricity sector.

These are directionally helpful.

But the current policy mix does not help green energy sources compete systematically with carbon-intensive energy sources. The price of coal and gas does not reflect the ‘cost of carbon’; nor does the price of diesel and petrol. This is despite the fact that the electricity sector accounts for about 30 per cent of emissions, and the transport sector more than 20 per cent.

It’s going to be extremely difficult to carve out a low-cost path to net zero without a carbon price correcting the cost of energy.

In the meantime, a mix of policies hurts the economy, because the incentive to reduce emissions differs across firms and sectors, raising the average cost of abatement.

And of course, current policies often create direct expenses – they burden the budget, rather than generating much-needed revenue.

In early 2024 Rod Sims and Ross Garnaut made the case for a Carbon Solutions Levy in a speech at the National Press Club – a relatively simple tax on fossil fuel production, applied at the source. Because about 80 per cent of Australia’s emissions are from the combustion of fossil fuels, it would deliver broad coverage. And it would raise revenue.

We have suggested that the price should rise progressively until it matches the price of permits in the EU Emissions Trading Scheme.

The government could use this revenue to compensate, or over-compensate, households for increases in energy costs, paying particular attention to low-income households.

There would be sufficient revenue to allocate across budget repair, social policies, and the adaptation measures that will become more important as temperatures rise.

Revenue could also be used to correct market failures. For example, there is a role for government support for green exports, while there is progress towards a system of international carbon prices. This wouldn’t just be good for Australia’s economy, but for the environment. Australia could make an outsized contribution to global decarbonisation by producing zero-carbon exports.

Australia faces some big policy challenges – big, and urgent. We need to reduce emissions and to raise revenue.

The best way to tackle both objectives is to introduce a simple tax on carbon, so polluters pay, so we can compensate households and support investments in long-term productivity and growth.

Thank you for your time.

Ingrid Burfurd

Carbon Pricing and Policy Lead